Menu

An anticipatory action pilot involves implementing a formal mechanism at the country level called an anticipatory action framework or plan. This predetermines who gets how much money, to do what, based on which signal so that a problem can be caught before it becomes a crisis.

All anticipatory action frameworks include a trigger mechanism, which goes hand in hand with the development of a crisis timeline. A trigger mechanism translates the characteristics of a shock (such as drought or flooding) and/or its impact (such as food insecurity) into technical specifications. These specifications are the basis for what the plan will pre-emptively respond to. However, the prediction of shocks is not an exact science, and it is important for all partners to acknowledge at the outset that the trigger data and forecasting is not always precise.

e.g. drought or flooding

The trigger for drought in Ethiopia functions as a two-step determination tool: it first determines the projected severity of humanitarian need, as captured by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), and it then determines whether drought conditions are projected.

The framework’s activation is triggered under the condition that the pre-determined threshold for both food insecurity and drought is met in at least one single region of Ethiopia. Acknowledging the multidimensional impacts of drought, food security phases are used as a proxy indicator for worsening conditions across multiple sectors. The framework uses food security projections with a lead time of three to six months and seasonal as well as sub-seasonal rainfall forecasts.

Flooding in Bangladesh is intense during some years, and it surpasses communities’ ability to cope. This causes deaths and the destruction of key infrastructure, livelihoods and homes.

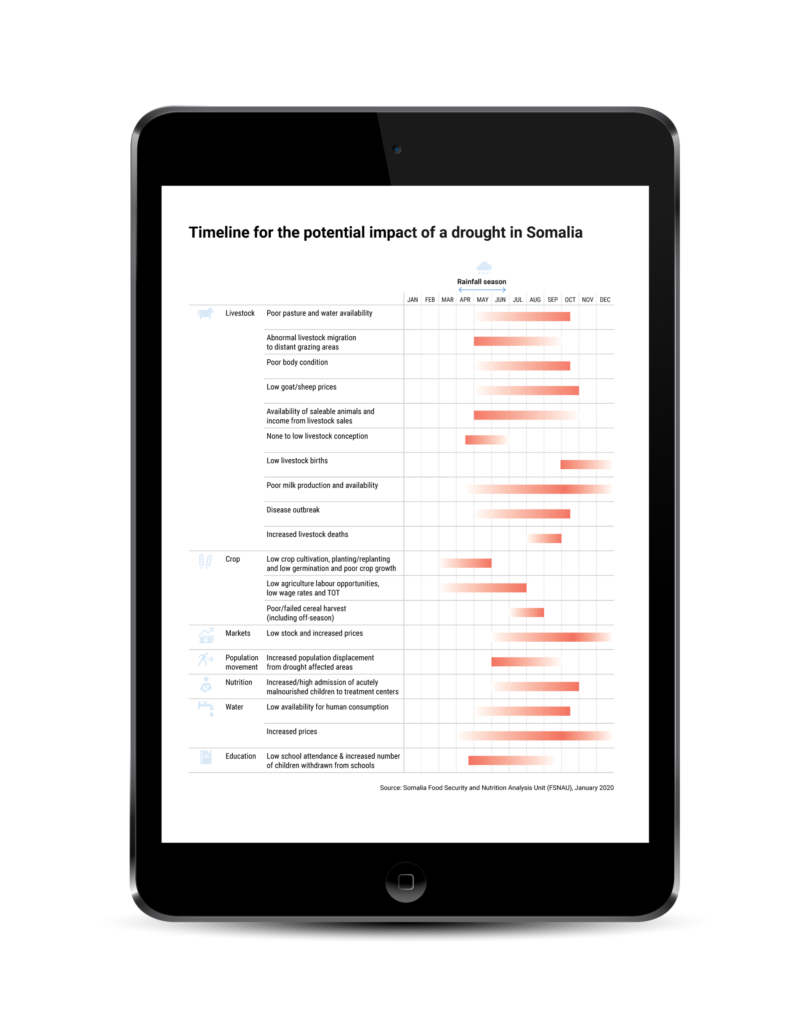

A crisis timeline aims to assess how the humanitarian crisis is likely to evolve once the shock occurs, the impact pathways and the consequences of the shock. The timeline also presents how humanitarian needs typically unfold, providing insight into how the consequences of a shock manifest themselves and when failures might occur, such as displacements and diseases. Development of the crisis timeline runs in parallel with developing the trigger mechanism. A crisis timeline is particularly important for slow-onset crises, e.g. seasonal shocks such as monsoons. A sudden-onset emergency may have a timeline that is measured in a matter of days between the readiness trigger and the shock itself.

Mapping out the crisis in a context-specific manner helps to understand the windows of opportunity for each activity. Once a crisis timeline has been completed, a separate calendar of activities can then be produced and overlaid with the crisis timeline so that the start and finish times of activities and impacts are clearly mapped out, in addition to lead-in times for financing and preparations.

The anticipatory action framework brings together a number of different planning elements already discussed in this toolkit. It is the central place where a plan is assembled, addressing different scenarios that may materialize at different times. Anticipatory actions will be planned that can interrupt the different pathways outlined in the crisis timeline by targeting populations most at risk of being impacted by a shock, and pre-identifying sectors. Plans include pre-agreed actions and processes for releasing finance.

Anticipatory action plans rely on up-to-date information such as lists of beneficiaries for cash distribution, contact details, contracts and weather predictions. Consider how regularly the plan should be updated to remain current and relevant at the time of activation.

Is the action effective in preventing or reducing the humanitarian impact of the shock?

In the case of a false alarm, will the actions benefit (rather than negatively impact) the targeted population?

Are markets functioning, is currency stable and are there supply chains, banking facilities and delivery routes for humanitarian assistance to reach affected areas?

Do governments and affected populations allow humanitarian assistance in the targeted areas and if so, is there a preference or restriction on certain forms of assistance (e.g. cash in hand)

Do agencies and the partners have capacity and operational readiness to implement the action effectively given the lead time and scale?

Is there physical and social access to assistance for all the impacted population, including the most vulnerable? Are there already existing programmes, either nationally or internationally led which have registration systems or beneficiary lists in place?

Is it possible to carry out the action effectively with the available forecast lead time, i.e. in the window of opportunity?

Each action plan addresses the following questions:

An anticipatory action framework seeks to serve as an overview of the anticipatory actions that are most likely to help mitigate the impact of a shock, stabilize vulnerable people and prepare for scale up for humanitarian action. The framework is intended to enable bilateral donors and pooled funding instruments to pre-commit finance and disburse funding when the above-outlined triggers are reached. Donors could include, but are not limited to, CERF, the World Bank’s Crisis Response Window, pooled funding mechanisms such as IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund, or the Start Network or Education Cannot Wait, Government funding, bilateral donors, and UN agencies’ internal reserve funds. When the need arises, each of these donors could finance part of this plan within their own established criteria and in complementarity.

The goal of anticipatory action is to release financing and deliver assistance before the crisis. OCHA uses CERF to disperse funds. There are two points during which CERF may disperse assistance: in readiness and in action/implementation.

An action trigger represents a post-disbursement ‘go’ versus a ‘stand-down’ moment. If the decision is to stand down, the donor will likely want to ensure that most of the disbursed funds are not automatically spent. In the pilots, CERF addressed this issue by requiring agencies to distinguish between readiness versus action costs, stipulating that action costs could be spent only if the trigger is reached.

Note that some activities fall beyond what CERF can finance, such as those concerned with infrastructure. However, it is important to design anticipatory action plans that incorporate everything that requires funding rather than what CERF can actually fund. This way all real funding needs are reflected in a plan. A full overview of the needs may allow for more funding to be crowded in later.

Fifth, and finally, we need to anticipate crises and act early. To do this we need to get the financing right. Over half of all crises are at least somewhat predictable and 20 per cent are very predictable. Yet less than 1 per cent of funding is pre-arranged. We need significantly more dedicated and predictable financing to bring preparedness to scale and to release funds before a disaster, rather than asking for funds when people are already suffering. For example, support from the United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund can prevent hunger and disease, improve people’s well-being and protect their incomes and livestock.

As anticipatory action and disaster-risk financing mature, there is a need to better understand and implement accountability, particularly towards people who are at risk. There is growing awareness of this, but application remains nascent. Accountability and a commitment to evaluation for those who directly benefit from actions will help to raise standards across the board. In some cases, anticipatory action provides more time to consult with people at risk and ask them what they need and when.

Further reading: Accountability in Disaster Risk Financing

Photo: FAO/Luca Sola

OCHA commissioned a local research team to study and learn from the experience of families affected by floods and dry spells in Malawi. The objectives of the study were to incorporate the knowledge and expectations of nearly 1,000 vulnerable households into the anticipatory action framework. Through the information collected, the study aimed to improve the pertinence, quality and timing of the framework being developed by the United Nations Country Team to predict floods and dry spells. In turn, this would trigger the release of CERF funding for the implementation of a pre-agreed plan, and pre-target the framework’s locations and beneficiaries to ensure it helps the most vulnerable and risk-exposed people.

The anticipatory action country pilots that OCHA launched in 2020 and 2021 are a steppingstone towards making anticipatory action more sustainable and scalable. A learning framework helps us to make logical choices about where to try anticipatory action next by assessing the feasibility, impact and quality of the anticipatory actions. OCHA used the learning framework for each pilot to dedicate time to reflect as a team on lessons learned, identify areas for greater attention or support and plan how to put learning into future action. A dedicated Monitoring and Evaluation Group can help input into the design and implementation of these learnings and place an emphasis on individual agencies carrying out monitoring and evaluation.

What determining factors make anticipatory action possible?

Can anticipatory action be brought to scale by complementing or being integrated into existing humanitarian planning tools and processes (e.g., ERP and HPC)?

How much impact does anticipatory action have compared to rapid response?

How can anticipatory action be done better?

Innovation takes courage. It involves taking risks and recognizing what we don’t know or understand. Challenges will arise, requiring openness and creativity to overcome.

Share, document and learn from challenges that arise. The greater the trust and transparency among partners in this collective effort, the more critical lessons can be integrated into current and future anticipatory action here and globally.

Learning requires intentional time spent reflecting, asking questions, and listening to and documenting perspectives, most importantly those of people impacted by disaster.

This helps to understand and share the benefits and challenges of designing and implementing anticipatory action frameworks in various contexts. Data collection may include bilateral conversations between:

Data collection could also include group “action learning reviews” on whether key assumptions are holding true.

This helps teams to understand what support was delivered by when, to how many people at what cost, and gain the self-reported beneficiary view of support. Indicators could be considered such as:

This provides an understanding of the impact of anticipatory action on mortality, morbidity, income and asset losses among beneficiaries relative to a control group. It should begin early in the planning phase in alignment with framework development. Key considerations:

Lesson learnt from pilots

Activation protocols: Once the trigger has been defined, monitoring begins, ideally in country. If the trigger is met, then protocol should already be in place (in the anticipatory action plan) to define which processes will take place to activate the plan, with the HC or RC responsible for the final decision to activate.

Service provided by

OCHA coordinates the global emergency response to save lives and protect people in humanitarian crises. We advocate for effective and principled humanitarian action by all, for all.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons by 4.0 International license.